David Jones got the call he will never forget in the early evening of June 24, 1997, from an acquaintance who raced on the local bike club with his son, Cooper.

“You need to go to the hospital right away. Cooper has been hurt,” the caller said.

“Did he break his arm?” Jones asked.

The caller wouldn’t say. Jones and his wife, Martha, raced to the hospital, hoping for the best but fearing the worst.

The events of the weeks and months that followed would forever change their lives–and make an indelible mark on Washington state’s bicycle safety laws. This is the story of a boy who loved racing bikes, the parents who fostered that passion, their quest to make the roads safer for people riding bicycles, and the creation of Washington’s Share the Road license plates.

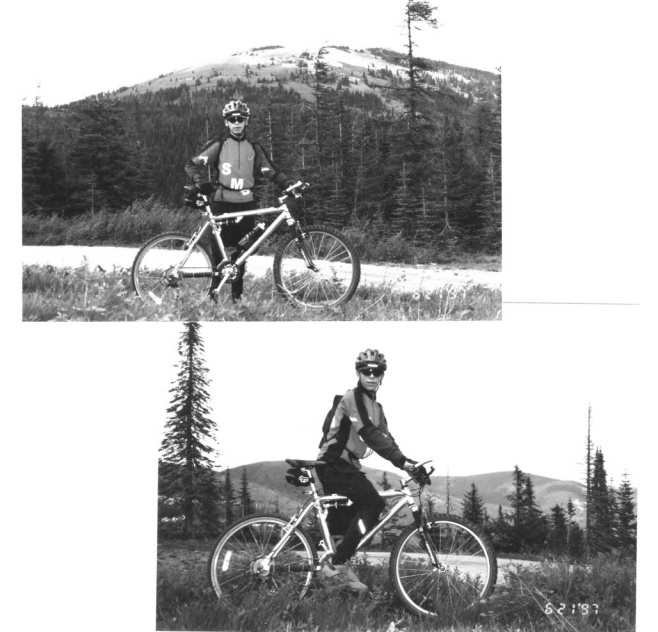

Cooper Jones took up bike racing in 1996 at the urging of his parents, who had watched him progress from speeding around their neighborhood to dropping them on long rides down the Centennial Trail in their hometown of Spokane. One day, they bumped into some members of the local Baddlands Cycling Club, and Martha convinced them to accept Cooper into their group.

“They were so kind to Cooper,” David Jones says. “Imagine being 11 or 12 and going on rides with adults who aren’t your parents and who think you are cool. He really got into it after that.”

Cooper was excited for the race on June 24, 1997, a time trial near Cheney, Wash. After only a year of racing he was among the points leaders on the team. David or Martha typically attended Cooper’s races, but this would be the first time he would compete without them.

Twenty-three years later, the anguish remains fresh in David Jones’ mind. “It’s still very hard to accept,” he told Cascade in an emotional interview.

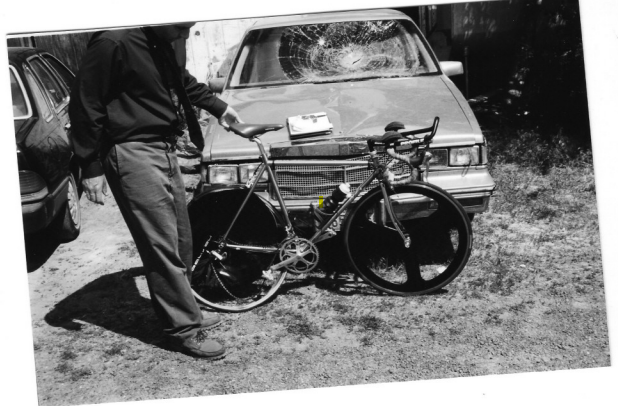

According to Jones and media reports from the time, Cooper was pedaling westbound along Highway 904 when the driver of a Cadillac passed a group of bike racers, then slammed Cooper from behind. He smashed into the windshield, and when the driver hit the brakes, Cooper slid off the hood and was run over, pinning him underneath the car.

The driver, a 66-year-old woman, had poor eyesight and other health problems, according to David Jones. “I don’t think she knew what had happened.”

Cooper was eventually extracted from underneath the vehicle, allowing first responders to perform CPR and transport him by helicopter to Deaconess hospital in Spokane.

That’s when David Jones got the call.

Mother and father arrived at the hospital to find Cooper unconscious and hooked to life support in the trauma unit. Cooper never regained consciousness. A week later, on July 2, 1997, his parents made the heartrending decision to remove Cooper from life support. “There was no hope that he would ever recover,” David Jones says.

Their grief was compounded in the months to follow, when, after a three-month investigation, the Washington State Patrol declined to criminally prosecute the driver, instead determining that she was guilty of second-degree negligent driving. The fine: $250.

The Jones family decided against suing the driver. “I have empathy for her, but you just think, there has to be a bigger repercussion for negligently causing a death. It’s still incomprehensible.”

In the aftermath of Cooper’s death, there was concern that the state would cancel all bike racing–and even large group rides such as Cascade’s Seattle to Portland. “There were no protocols in place,” says Phil Miller, a transportation planner at the University of Washington and a certified bike racing official who was involved in discussions at the time.

The Jones family worked with the bike racing community to bring state agencies to the table in 1998 to create the Washington State Bicycle Racing Guidelines, which enabled bicycle events such as STP and other Cascade major group rides and events to continue.

Updated in 2010, these guidelines remain in effect today. “They have become a national standard,” says Miller, noting that at least six states have replicated Washington’s guidelines. “It’s much safer today.”

Hoping to prevent other families from suffering the same grief, the Jones family teamed up with the Bicycle Alliance of Washington (now called Washington Bikes) and convinced legislators to introduce a bill that was signed into law in 1998. The Cooper Jones Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Education Act, among other things, mandated that any driver at fault in a fatal crash must be re-tested by the Department of Licensing to ensure they are capable of driving safely. The driver who struck Cooper was “the poster child for someone who shouldn’t have been driving in the first place,” David Jones says.

The Cooper Jones Act also created a state commission, then known as the Cooper Jones Bicyclist Safety Advisory Council, to recommend safety and educational improvements to make the roads safer for people riding bikes.

The only problem: there was little to no funding for the commission, which remained largely toothless for many years, even taking a six-year hiatus until 2013 when it was reconvened. Today, it is known as the Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety Council, and it advocates for the safety of people biking and walking.

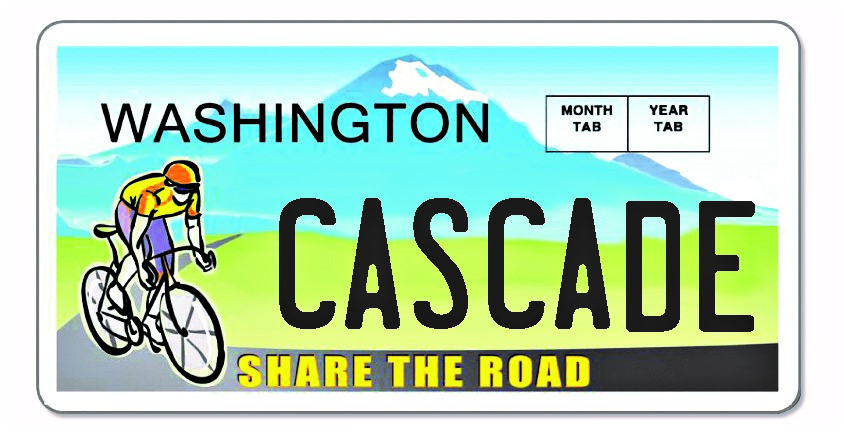

“The Legislature was not very friendly to bicycling back then,” says Cascade member Don Martin, who is credited with coming up with the idea for Washington’s Share the Road plates. He had heard about Florida’s Share the Road license plates and felt they would be popular here. In the early 2000s, he convinced a state senator to introduce a bill to create a similar plate in Washington as a way to generate revenue for bicycle safety and to create a visual reminder for people driving to be alert for bikes on the road.

“Because of that terrible incident, and the fact the driver got away with it, I thought something had to be done,” Martin, now 92, says. “Nobody in the Legislature or the State Patrol had any idea how many bicycle riders there were in Washington, and we needed something to identify who we are.”

The bill failed to pass in multiple legislative sessions due to financial concerns. In 2005, a compromise was reached whereby supporters posted a bond to cover the costs of creating the Share the Road plate program, and in 2006 the plates went on sale–inspiring many other states to create bicycle advocacy plates.

Today, about half of U.S. states offer Share the Road license plates.

While demand was initially high, sales have waned in recent years.

Approximately 2,800 Share the Road plates were registered in Washington in August of 2020. Costing $77.25 for a passenger vehicle, each plate generates $28 for Cascade, which spends the money on safety, education, and policy measures meant to reduce collisions between people driving automobiles and people walking and bicycling. Last year, Cascade received about $85,000 from Share the Road plates.

The need for road safety and zero traffic fatalities of walkers and bicyclists remains great. Nearly a quarter of all traffic fatalities, and 20 percent of all serious traffic related injuries, were to people walking or biking, according to the 2019 Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety Council annual report, which notes that the number of people killed while walking or biking was at its highest number in more than 30 years.

In light of these statistics, Cascade, as well as the Jones family, is urging its members and supporters, and everyone who rides bikes, to consider purchasing a Share the Road plate. Cascade hopes to double sales of the plates to boost revenue for its advocacy programs.

“We have them on all three of our vehicles,” David Jones says. One of those vehicles is a camper van that Cooper inspired his parents to buy. “His dream was to get a car that he could sleep in, so he could go to bike races,” Jones says. The van’s license plate carries the enthusiastic phrase that Cooper, the boy who “had it all,” wanted to have on his own vehicle: GOTITAL.

David Jones, now 70 and recently retired, looks forward to hitting the road in the camper van, exploring new places by bike as Cooper hoped to do.

“Things are better now but you never truly get over it,” David Jones says. “We see people that Cooper went to school with who are now in their mid-30s, and who have families of their own. It’s a constant reminder of what should have been.”

Cooper’s legacy lives on in the Cooper Jones Act, landmark legislation that, in addition to leading to the creation of the Share the Road plates, opened the door to many other initiatives that continue to protect vulnerable street users to this day, including:

Adding bicycle and pedestrian safety into the state’s drivers’ education curriculum;

- Institutionalizing the Safe Routes to Schools program;

- Elevating texting and cell phone use while driving to a primary traffic offense;

- Passage of the Vulnerable User and Neighborhood Safe Streets bills.

In 2017, Washington Bikes pushed legislation that included dedicated funding for the Cooper Jones council, which was approved. Washington Bikes has a seat on the Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety Council, and continues to push for stronger safety laws that protect people bicycling and walking.

“The legacy of the Cooper Jones Act is large,” according to Miller, who says it helped cement the “right to the road” for people on bikes. “It also established that providing safe personal mobility was part of the state’s responsibility. The Jones family never lost focus on making some good out of their pain.”

Resources:

Order your Share the Road plate.

2019 Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety Council annual report, which cites that in 2018 16 people on bikes and 103 people walking were killed by motor vehicles.

Link to an essay Cooper Jones wrote the year before his death, where he describes his desire to become an Olympic bike racer.

At least 24 states now offer Share the Road plates, according to a 2017 Bicycling story.

In 2019, the Legislature created Target Zero, which establishes that people who walk or ride bicycles are one of the highest priority populations for traffic safety. The Cooper Jones Active Transportation Safety Council and Washington Bikes are working to achieve Target Zero, which dictates that no deaths are acceptable on the state’s roadways.